Making sense of Roman finds in the West: The Roman Object Revolution

In my book The Roman Object Revolution (Amsterdam University Press, 2019), I explore Rome’s impact on people in late Iron Age northwest Europe by comparing the contexts and combinations of an influx of new objects. By taking a cross-provincial approach to archaeological material from Britannia, Gallia Belgica and Germania Inferior, spanning Belgium, Britain, France, Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, the book underlines the benefits of thinking about material culture in terms of a connected Roman empire.

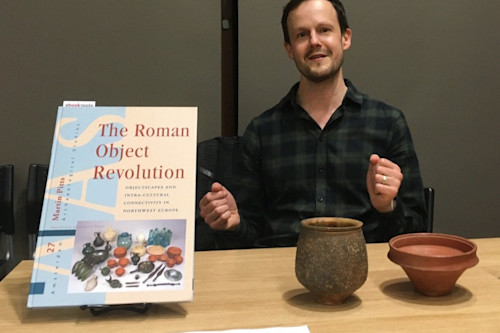

As Roman expansion connected the object worlds of the Mediterranean and the ‘barbarian’ northwest, the ensuing ‘object revolution’ had two major impacts. In the short-term, the appearance of vast numbers of new standardised objects of Mediterranean design helped to create new possibilities for cultural sharing, as well as maintaining distinct local identities. For example, pots like the terra rubra cup (pictured) were placed in the graves of local people in virtually identical combinations in Essex (SE England) and Luxembourg, implying a close cultural connection. Such combinations were not for everyone, and were scarce, however, in contemporary cemeteries in the Netherlands. By looking at the ‘Big Data’ of such object associations, the book highlights the existence of large-scale cultural networks across perceived boundaries (i.e. the Channel), both before and after Roman conquest.

Mass-produced objects as historical agent provocateurs – a terra rubra cup and a colour-coated beaker. Copyright: Martin Pitts.

In the longer-term, the ‘object revolution’ took new directions. One such change involved the everyday objects used by the Roman military. When Roman soldiers first arrived in northwest Europe, most had been recruited from the Mediterranean, bringing with them a taste for Mediterranean food and drink. However, over time, recruitment became increasingly local, with societies like the Batavi (Netherlands) and the Nervii (France/Belgium) providing significant manpower as early as the first century AD. While military service provided a way for such people to ‘become Roman’, the Roman military also changed through the influence of its recruits. In this way, it did not take long for pots like colour-coated beakers (pictured) became part of military life, being better suited for drinking northern European beer, as opposed to wine. Changing fashions of everyday objects like this help to illustrate how northwest Europe was Romanised, while fundamentally changing what it meant to be Roman at the same time.